Does “Zero Risk” Investment Strategy Really Exist?

Written by Arthur Lei on 2019-07-19

6:00PM, Sept 23rd, 1998. Former senior Federal Reserve official Peter Fisher breathed a sigh of relief.

After two days of intense negotiation, 14 financial institutions finally reached an agreement of US$3.6 billion to bailout Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), the largest hedge fund in the US at the time. Many believed if no bailout happened that the fall of which could potentially trigger a full scale financial crisis.

Let’s rewind the clock back to the beginning. Our story started as a partnership between Wall Street executives and world leading economists, who gathered together to exploit arbitrage opportunities to generate ultra-high “zero risk” returns.

The Dream Team

After leaving Solomon Brothers in 1993, John Meriwether founded LTCM in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Meriwether was the head of fixed income arbitrage sales at Solomon, and was said to contribute over 80% of company profit. As natural as it seemed, Meriwether brought his strategy to LTCM, together with his star trader comrades, and two future Nobel Laureate in Economics: Robert Merton and Myron Scholes.

With his charm, the former Fed Chair David Mullins also joined LTCM as a partner. Meriwether truly formed a Dream Team that the hedge fund industry had never seen.

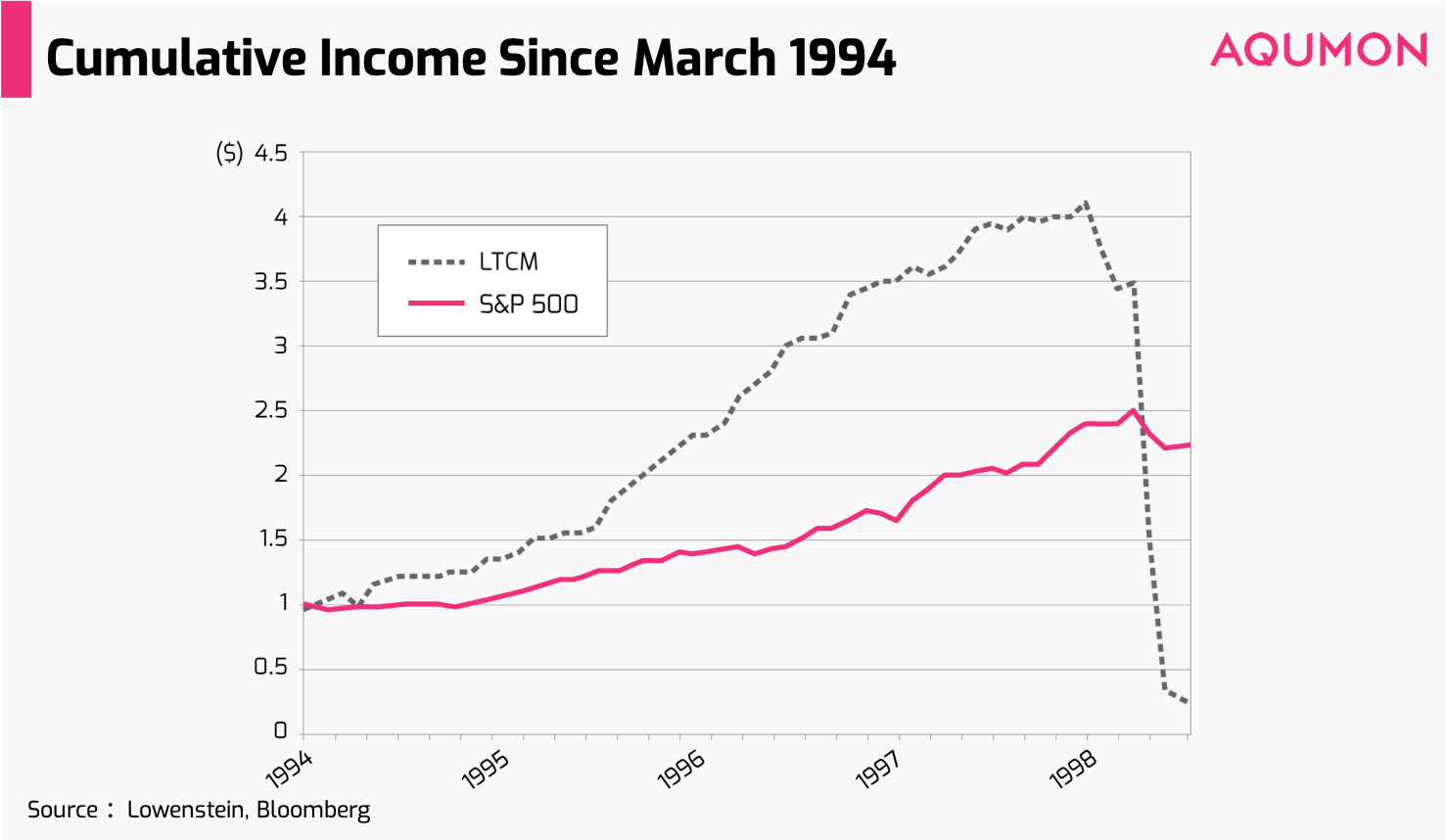

With the influential team and the aggressive sell by Merrill Lynch, LTCM raised over $1 Billion in the first week, and paved its way as the leading hedge fund in the industry for the next three glorious years.

In the first year, LTCM set its performance fee to 21%; the number soon raised to 43% in the second year, and 41% in the third year. Indeed, LTCM set its performance fee based on the promise of 25% annual return, a number that intrigued investors to pour gold into the magical fund.

The Essence of Arbitrage

The dashing performance of LTCM could be contributed to its core trading strategy—fixed income arbitrage.

Based on the trading strategies from Solomon Brothers, two Nobel Laureates further refined the LTCM strategy with complicated mathematical models.

The essence of the fixed income arbitrage was simple: assume that two classes of assets with the same cash flow will eventually convert in price. The strategy is designed to take advantage of price discrepancies in the short term due to liquidity constraints.

Highly liquid assets generally have higher price, and vice versa, which is the backbone to the theory of Liquidity Arbitrage.

Such price discrepancies provides an opportunity to locate assets with similar cash flows, take a long position in low liquidity assets and short high liquidity assets.

LTCM succeeded in exploiting arbitrage opportunities under its guiding theory and trading strategies, and some classical cases include the use of arbitrage for US Treasury notes with different maturity, as well as similar bonds with different issuers.

At the beginning, those arbitrage strategies did work, and brought huge profits for the company together with higher than expected return for investors.

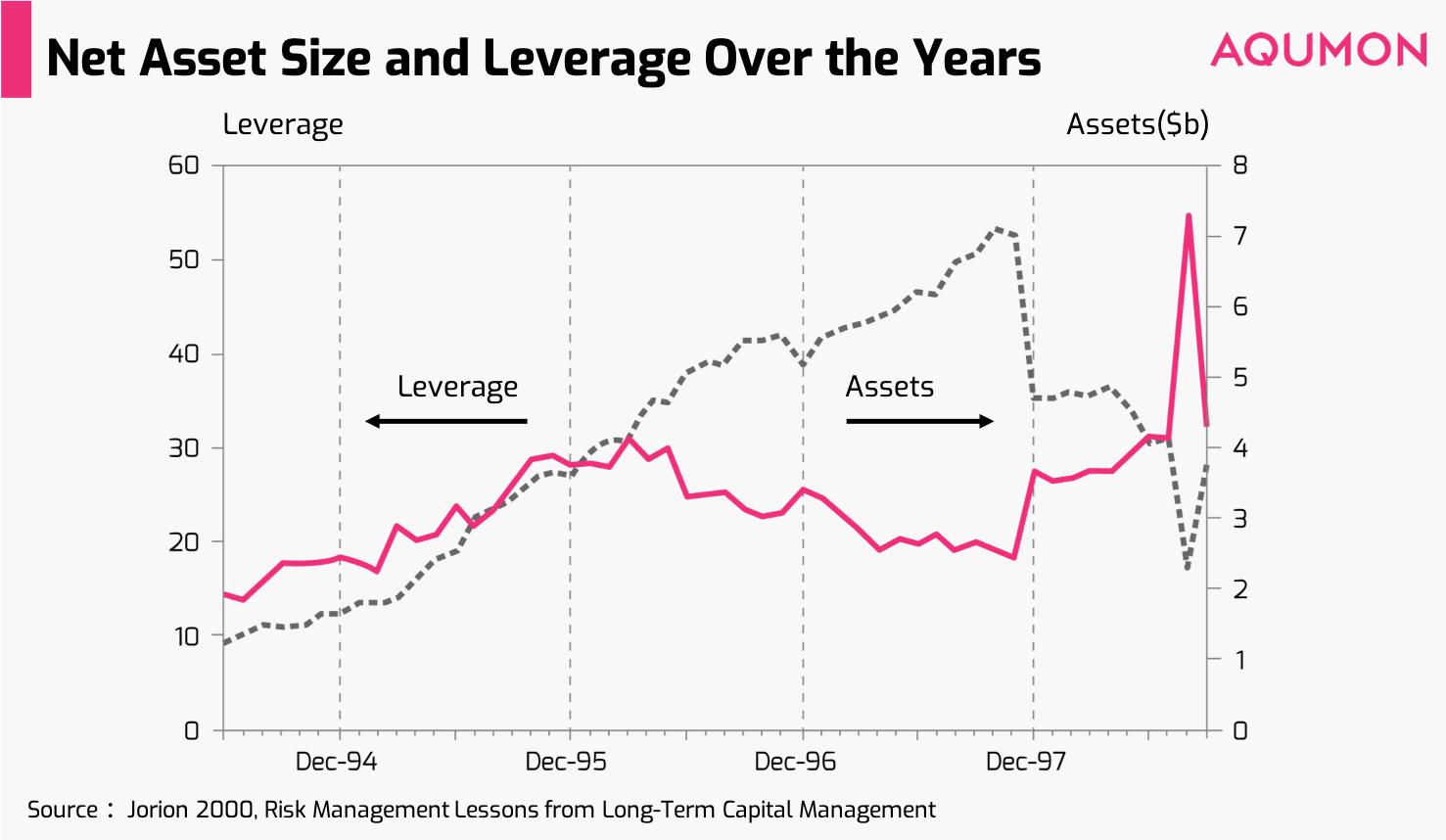

By the end of 1997, LTCM held a net asset worth of US$7 billion and total assets of US$100 billion, twice the size of the largest mutual fund Fidelity and quadruple the size of the second largest hedge fund in the industry.

Temptation of the Frenzy

The overturn of LTCM was partially due to the unpredictable nature of the financial market.

LTCM was exceptionally successful, thus its strategy attracted a large number of imitators.

“Everyone started imitating our strategy, and the profit margin of the fixed income arbitrage was diminishing,” recalled Rosenfeld, former trader at LTCM.

In 1997, the after-fee return of LTCM was 17.1% while S&P 500 Index was up by 31.0%. LTCM returned $2.7 billion in funds to investors at the end of 1997, fearing that investors would question the reason why the fund yield a lower than expected return that did not match the high performance fee charged by LTCM.

To boost its return, LTCM started to increase the use of leverage.

For every $1,000 in capital: if you earn $1, the return is 0.1%; if you borrow $999,000, then you could earn $1,000. Assuming the interest cost is $500, the rate of return could reach as high as 50%.

There are two critical criterias to ensure that this strategy works:

1) Firstly, the strategy needs to be particularly stable, plus a controllable stop-loss strategy.

Otherwise, losses and gains would both be amplified. In the previous example, if there is a loss of $0.5 for every $1,000 invested, the $1,000 initial capital would be all lost.

2) Secondly, the return of the strategy has to be higher than the borrowing cost, i.e. the interest rate. In the previous example, if the interest rate is higher than 0.1%, the use of higher leverage could lead to larger losses.

Based on the mathematical model at the time, fixed income arbitrage was considered risk free. This led LTCM to increase its leverage over time. As LTCM was performing extremely well, and the invested assets were highly liquid, its borrowing cost was relatively low.

After returning $270 million capital to its investors in 1997, LTCM increased its leverage from 18:1 to 28:1. At one point, LTCM had only US$12 billion net assets, but its exposure was over US$1.25 trillion, and the leverage was over 100:1.

Downfall

For LTCM, the biggest problem of the mathematical model was the dependency of the hypothesis. There are a few fundamental assumptions:

1) The price of the same cash flow must converge, and the current liquidity premium is only temporary;

2) The difference in liquidity brings liquidity premium;

3) The difference in liquidity itself is exogenous.

Such a hypothesis naturally ignores one of the most basic questions: for two groups of assets with the same cash flow, why does the one with higher liquidity attract more investors than the less liquid one?

In fact, the market had answered this question.

In the first half of 1998, crude oil prices fell by 14%, and the Russian stock market, dominated by crude oil exports, also plummeted (and eventually fell by 75% during the year). In order to hedge the risk, investors sold Russian securities, and Russian short-term government bond yields soared to 200%.

The spread between Russian government bond yield and US Treasury bonds yield did not converge over time, but diverged dramatically.

This caused huge losses for the LTCM portfolio, which held long-term emerging market bonds while shorting US Treasury bonds. In June 1998, the monthly loss of LTCM portfolio exceeded 10%. In August, Russia announced the devaluation of Russian Ruble and suspended the repayment of more than 281 billion rubles (US$13.5 billion) of Russian government bonds. The default caused greater losses for LTCM. On August 21 alone, the fund lost US$550 million.

Such losses caused a decline in the net value of the fund and investors rushing to withdraw their funds. By the end of September, LTCM’s net assets shrank to US$400 million, while liabilities exceeded US$100 billion.

If LTCM declared bankruptcy and forced the liquidation of all its positions, the outcome would cause a devastating disaster within financial markets.

Emerging market treasury bonds, short-term maturity US Treasury bonds and stakes in M&A target companies will all be affected by the plunge; while short-selling US Treasury bonds and M&A acquiring companies will be affected by the surge.

The skyrocketing and slumping of asset prices would eventually lead to a systemic financial crisis. This happened when Lehman Brothers collapsed in 2008. Another example was due to the large number of short-selling of Volkswagen stock and long Porsche positions, Volkswagen’s share price soared and Porsche share price plummeted, which led to the failure of Porsche acquisition of Volkswagen and the Volkswagen anti-takeover situation.

Such effects are common in any financial crisis.

In order to avoid the financial tsunami caused by the collapse of LTCM, the Fed finally came forward and called 16 institutions to fund the bailout. Two days after the negotiation, 14 financial institutions eventually agreed to jointly bailout of US$3.6 billion to acquire more than 90% of LTCM stake.

Does Risk-Free Arbitrage Really Exist?

The biggest lesson from LTCM case was the ignorance of risks while overly depending on the mathematics model. From the perspective of model, fixed income arbitrage was risk-free.

Generally speaking, arbitrage means getting something from nothing. With zero input, investors may get return or nothing without a loss. However, fixed income arbitrage is not risk-free. In fact, LTCM was always exposed to both credit risk and liquidity risk.

This reminds us that when creating an arbitrage strategy, the first step is to analyze the logic behind the arbitrage opportunity.

Generally speaking, arbitrage opportunities are quite rare. In most cases, short-term asset pricing deviating from its intrinsic value will eventually convert to that value in the long term. Pricing discrepancies exist in the market because of irrational factors and information constraint.

Indeed, strategies like fixed income arbitrage have no pricing bias. The emerging market sovereign bonds had lower prices than the corresponding US Treasuries for a reason. The primary cause for the liquidity difference derives from lower liquidity and higher credit risks.

To some extent, the fixed income arbitrage is a beta strategy that obtains excess return by bearing the default risk in the future.

Additionally, even when an arbitrage opportunity does exist, there are two issues with the short-term mispricing.

1) Limited Time for Arbitrage

Arbitrage opportunities are rare and could disappear after the trade. In most cases, only frequent trading could capture arbitrage opportunities.

2) Risk Management

In unusual situations, as in the LTCM case, when the arbitrage opportunities are exploited, investors face larger short-term losses.

When investing with leverage, the short-term loss leads to the risk of mandatory liquidation, i.e. the liquidity risk. Hence, when applying arbitrage strategies, we need to consider extreme market conditions, and thus it is more rational to choose strategies with higher probabilities of return.

Disclaimer

Viewers should note that the views and opinions expressed in this material do not necessarily represent those of Magnum Research Group and its founders and employees. Magnum Research Group does not provide any representation or warranty, whether express or implied in the material, in relation to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information contained herein nor is it intended to be a complete statement or summary of the financial markets or developments referred to in this material. This material is presented solely for informational and educational purposes and has not been prepared with regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any specific recipient. Viewers should not construe the contents of this material as legal, tax, accounting, regulatory or other specialist of technical advice or services or investment advice or a personal recommendation. It should not be regarded by viewers as a substitute for the exercise of their own judgement. Viewers should always seek expert advice to aid decision on whether or not to use the product presented in the marketing material. This material does not constitute a solicitation, offer, or invitation to any person to invest in the intellectual property products of Magnum Research Group, nor does it constitute a solicitation, offer, or invitation to any person who resides in the jurisdiction where the local securities law prohibits such offer. Investment involves risk. The value of investments and its returns may go up and down and cannot be guaranteed. Investors may not be able to recover the original investment amount. Changes in exchange rates may also result in an increase or decrease in the value of investments. Any investment performance information presented is for demonstration purposes only and is no indication of future returns. Any opinions expressed in this material may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by other business areas or groups of Magnum Research Limited and has not been updated. Neither Magnum Research Limited nor any of its founders, directors, officers, employees or agents accepts any liability for any loss or damage arising out of the use of all or any part of this material or reliance upon any information contained herein.